Erlang is a functional programming language developed at the Ericsson Computer Science Laboratory in the late 1980s. The language has recently gained some attention for its concept of concurrency (it implements the actor model) and being the inspiration of Scala. Erlang is great at concurrency and building scalable, fault-tolerant applications. Have you ever seen 2012? When Cusack phones while the whole world collapses? I bet there was some Erlang involved!

The characteristics of Erlang are:

- higher-order functions

- scalability

- soft realtime properties

- processes and message passing

This introduction to Erlang was written by Filip for our documents.

Getting Erlang

Erlang is available at:

Binaries are available for Windows or you can compile from sources, which is pretty easy. Prebuilt packages should be available for most Linux distributions (I know from Debian, Ubuntu and Gentoo).

You start the erlang shell by typing erl in a terminal and leave it by pressing Ctrl + G followed by a q.

Programming Erlang

Variables

In Erlang a variable always starts in uppercase. Assigning a value is done with the = operator. Erlang uses Single Assignment for variables. It is not as strange as it seems, because C++ also supports single assignment through the const keyword (or in Java it is final). Just think of single assigment in a mathematically sense, so you can never write A = A + 1, but you have to write B = A + 1. This simplifies debugging and removes side effects (especially for concurrency) yet it sucks sometimes.

1> Q = 4683.

4683

2> A = 30484.

30484

3> Q = A.

** exception error: no match of right hand side value 30484

4> f().

ok

5> Q.

* 1: variable 'Q' is unbound

Atoms

Atoms start with a lowercase letter or are written inside of apostrophes. Think of atoms as unique identifiers in records or lists for example. You'll find atoms very often in Erlang as key-value pairs for pattern matching. Read on, you will understand it in a second.

By the way: Boolean is no datatype in Erlang, but is represented with the atoms true and false.

1> atom1.

atom1

2> 'Atom2'.

’Atom2’

3> test@web.de.

'test@web.de'

4> A = 3.

3

5> A =:= A.

true

Numbers

Integer numbers in Erlang are written as BASE#VALUE. Default is base 10:

1> -10.

-10

2> 2#101010.

42

3> 16#CAFEBABE.

3405691582

4> 16#CAFEBABE + 32#SUGARBABE.

31838067516460

Floating point numbers are represented as IEEE 754 64bit floating point numbers (52bit mantissa, 11bit exponent):

1> 1.2E10 - 1.2E-10.

1.2e10

2> 1.231.

1.231

Strings

A string is not a datatype in Erlang, but just a list you write inside double quotes ". This makes it possible to work with all primitives Erlang has for lists, but the downside is that each character takes 8 bytes and we end up with O(n) time complexity for access on elements. So please: don't expect Erlang to perform like Perl.

Because a string is represented as a list you can do things like this:

1> lists:append("cafe","babe")

"cafebabe"

2> lists:subtract("cafebabe", "cafe").

"babe"

3> [H|T] = "cafebabe".

"cafebabe"

4> H.

99

5> <<H>>.

"c"

6> T.

"afebabe"

7> length(T).

7

A simple way to strip characters off a string is given by:

1> A = "something with two\n\n".

"something with two\n\n"

2> string:strip(A, right, $\n).

"something with two"

Tuples

Tuples are like records in other programming languages and you may know lists and tuples from everyday Python programming already. Tuples in Erlang are denoted with curly braces {, } and store a fixed number of data types. Access is in constant time.

Tuples are extensively used within Erlang to return status and Data as {status, Data}. Let's open the documentation at a random point! file:get_cwd() for getting the current working directory is described as:

[...]

Exports

get_cwd() -> {ok, Dir} | {error, Reason}

Types:

Dir = string()

Reason = posix()

[...]

So this method either returns the tuple {ok, Dir}, where Dir is the working directory of the server or returns the Reason for an error. You will see this very often in Erlang programs:

1> {ok, Path} = file:get_cwd().

{ok,"/home/philipp"}

2> Path.

"/home/philipp"

Here are some more examples for tuples:

1> A = { 'Map', 16#BABE }.

{'Map',47806 }

2> tuple_size(A).

2

3> element(2,A).

47806

4> B = setelement(1,A,'Reduce').

{'Reduce',47806}

Lists

Lists in Erlang have varying length and are denoted by brackets [````]. Lists are always composed by a head of the list and tail. List comprehenshion is also powerful tool:

1> [ 'Map', 16#BABE ].

[ 'Map', 47806 ]

2> length([ 'Map', 16#BABE ]).

2

3> [ test1 | [ test2 | [] ] ].

[ test1, test2 ]

4> Quad = [ X*X || X<-[1,2,3,4] ]

[1,4,9,16]

Pattern Matching

Erlang uses Pattern Matching for the assignment of variables, which makes it possible to extract values of complex structures:

1> {person, Name, en} = {person, 'Thomas', de}.

** exception error: no match of

right hand side value {person,'Thomas',de}

2> {person, Name, de} = {person, 'Thomas', de}.

{person,'Thomas',de}

3> Name.

'Thomas'

Now let's get back to the Head and Tail example from above and see how Pattern Matching works for it:

1> [Hd | Tl] = [test1, test2, test3].

2> Hd.

test1

3> Tl.

[test2, test3]

Functions

Functions in Erlang have to be defined in a module. This is nothing complicated. I wanted to write some more stuff about it, but Paolo has written a good article in his blog:

So open your favourite editor and paste:

-module(mymap).

-export([mymap/2]).

mymap(Fun,[]) ->

[];

mymap(Fun,[Hd|Tl]) ->

[Fun(Hd) | mymap(Fun,Tl)].

Save it as mymap.erl and open up a terminal. Change to the directory you saved the file to and start the Erlang shell. To compile the module you write:

> c(mymap).

or you use erlc from command line:

philipp@banana:~/src/erl$ erlc mymap.erl

Now you can have fun!

1> Square = fun(X) -> X * X end

#Fun<erl_eval.6.13229925>

2> mymap:mymap(Square, [1,2,3,4]).

[1,4,9,16]

You see: Functions are also datatypes in Erlang.

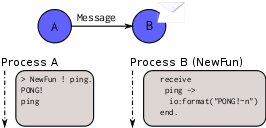

Concurrency: Message Passing

When talking about Erlang, we are talking about the language and the Erlang Virtual Machine (VM) aswell. People love Erlang due to its concept of handling concurrency and its simple yet powerful primitives to create processes and communication between them.

Erlang processes have no shared state and communicate with messages, this is also called Message Passing in computer science. On http://www.defmacro.org/ramblings/concurrency.html is a very well written article regarding everything you would like to know, http://pragprog.com/articles/erlang is also a good read.

Erlangs built-in function spawn is used to create a process within the Erlang VM. Erlang processes are no Operating System Processes nor Threads, just lightweight: a function with a process identifier.

You can send a message to a process by using the ! mark and receive messages with the blocking receive statement. Let's look at an example.

Imagine we have a function, that waits for an atom ping to output a PONG to the screen. You can type this in the Erlang shell, we assign the process to the variable NewFun, you can see the unique process id <0.48.0> returned by the Erlang VM.

Now we can send a message to the process by writing NewFun ! ping and that's it. PONG!

1> NewFun = spawn(fun()-> receive

2> ping -> io:format("PONG!~n")

3> end end ).

<0.48.0>

4> NewFun ! ping.

PONG!

ping

Further Reading

- Cesarini, Francesco and Thompson, Simon. Erlang Programming Amazon

- Armstrong, Joe. Programming Erlang: Software for a Concurrent World Amazon

- Armstrong, Joe. Making Reliable Distributed Systems in the Presence of Software Errors PDF

- Trottier-Hebert, Frederic. Learn You Some Erlang. http://learnyousomeerlang.com